Skelly Wright: the early years

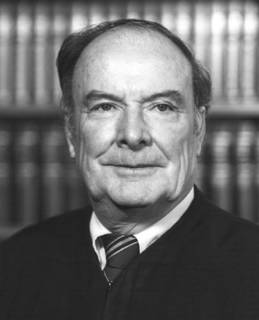

People occasionally wander here from searches for "Skelly Wright," and at least one commenter seems to think that I am Skelly Wright, owing to the icon there in the upper right-hand corner. So, as a public service, here is a bit of history about this blog's patron saint, the Honorable J. Skelly Wright.

People occasionally wander here from searches for "Skelly Wright," and at least one commenter seems to think that I am Skelly Wright, owing to the icon there in the upper right-hand corner. So, as a public service, here is a bit of history about this blog's patron saint, the Honorable J. Skelly Wright.

It was 1946, and New Orleans had won the war. After a "perfunctory" trial, Willie Francis, a 16-year -old African-American, had been convicted of murder of a white man by the State of Louisiana and sentenced to die in the electric chair:

But at the moment of electrocution, the chair malfunctioned: some current flowed through Francis’s body, enough to cause intense pain but not enough to kill him. Neither of the men who had installed the portable electric chair were electricians, and the actual executioners were probably drunk at the time they threw the switch. Prison guards dragged Francis off to his cell and called an electrician. Meanwhile the NAACP and others mounted a crusade to prevent the state from trying to electrocute him a second time.

His lawyer at the U. S. Supreme Court: New Orleans native J. Skelly Wright, age 35:

Skelly Wright, then in private practice, argued the case before the Supreme Court. He framed the issue as whether the electrocution retry would violate the Fifth Amendment’s double jeopardy provisions, the Eighth Amendment’s ban on cruel and unusual punishment, or the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process and equal protection requirements.

To no avail:

The state of Louisiana again electrocuted Willie Francis, this time effectively, on May 9, 1947. For him, the travesty of reason in judicial decision-making had come to an end, but the Justices were not yet done with the questions that his fate had placed before them so poignantly.

The Supreme Court bungled Willie Francis’s appeal as badly as the drunken executioners had bungled the first electrocution try. The resultant mischief lives on. Later courts recurrently cite Francis v. Resweber, along with In re Kemmler, as authority for the proposition that the Eighth Amendment does not bar death by electrocution, shutting their eyes to mounds of empirical and graphic data demonstrating beyond any doubt that, far from being "instantaneous and painless", as numerous judges have termed it, death by electrocution is horrifyingly violent, prolonged, and painful. Though no opinion in Francis addressed that issue, the case lives on, misapplied to perpetuate state torture.

Bonus link goes to "Professionalism: Lawyers as Heroes, Villains and Fools" by Roger A. Stetter (pdf file). Skelly Wright is in the first category.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment